s Sublevels are Spherically Shaped

All ℓ = 0 electron waves are s waves, or waves from the s sublevel, and they all describe electrons in s orbitals. As suggested in the previous section, all electron waves from the s sublevel have the same overall shape, regardless of the value of n, regardless of their size, and regardless of the number of nodes they contain. s orbitals always correspond to spherical waves. The quantum numbers n = 1 and ℓ = 0 describe a small spherical wave with no nodes, the quantum numbers n = 2 and ℓ = 0 describe a larger spherical wave with a single node, and the quantum numbers n = 3 and ℓ = 0 describe an even larger spherical wave with two nodes. These waves all look slightly different, as shown in Figure 6.16.

Figure 6.16: Various s orbitals. All of these orbitals have ℓ = 0, but they have different values for n. The first orbital has n = 1, and thus is small and has no nodes. The second orbital has n = 2, and thus is larger and has one node. The third orbital has n = 3, and thus is even larger and has two nodes.

Nevertheless, they are all spherical, because they all have ℓ = 0. Their shapes don't change – only their sizes and the number of nodes that they contain.

Now if you think back to an earlier lesson, you might remember something special about the different orientations of a spherical wave. Do you remember what happened when we rotated the spherical wave so that it pointed in different directions? It ended up looking the same, didn't it! No matter which way you rotate a sphere, it always looks the same. So how many different ml values do you expect for a spherical wave? One, of course! Now that you know spherical waves all have ℓ = 0, you can use your rules for ml to figure out exactly how many different ml are allowed. If you look back to Example 4 in the previous lesson, you'll see that we actually did that calculation. It turned out that there was only one allowable value for ml, and that was ml = 0. In other words, there is only one orientation of a spherical wave. It all makes sense!

So what does a spherical wave really mean? It means that your probability of finding an electron at any particular distance from the center of the atom only depends on the distance, and not on the direction. You can see this in Figure 6.17.

When the Azimuthal Quantum Number is 1, then ml Can Only Be -1, 0 or +1

All ℓ = 1 electron waves are p waves, or waves from the p sublevel, and they describe electrons in what are known as p orbitals. Unlike s orbitals, p orbitals are not spherical, so they can have different orientations in space. Now that you know all p orbitals have ℓ = 1, you should be able to figure out exactly how many different p orbital orientations exist by using your rules for ml. (ml is the quantum number associated with the orientation of a particular orbital). Let's figure it out.Example 1 How many different p orbital orientations are possible? Solution: ℓ = 1 From now on, whenever you're told an electron is in a p orbital, you're expected to know that electron has the quantum number ℓ = 1. The question asks how many p orbital orientations are possible, but what it's really asking is how many different ml values are allowed when ℓ = 1. We've already done this type of problem. 1. Find the minimum value of ml.

|

The p Orbitals are Often Described as Dumb-bell Shaped

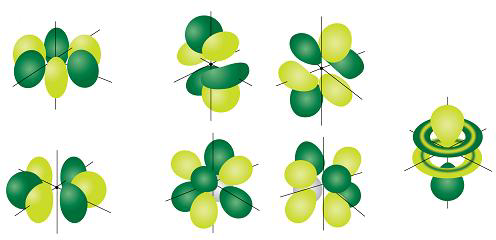

Even though you know that there are three possible orientations for p orbitals, you can't really predict their shape unless you know a lot more about mathematics, physics, and wave functions. When scientists use the wave function to draw the shape of an electron's p orbital, though, they always end up with is something that looks a lot like a dumb-bell. Not only that, the three different p orbitals (one with ml = −1, another with ml = 0, and the third with ml = 1) turn out to be perpendicular to each other. In other words, if one p orbital points along the x-axis, another p orbital points along the y-axis, and the third points along the z-axis. Scientists typically label these three orbitals px, py, and pz respectively. The below figure shows each of the three p orbitals separately, and then all three together on the same atom.Sometimes we get so caught up thinking about electron wave functions, and electron orbitals, that we forget entirely about the atom itself. Remember, electron standing waves form because electrons get trapped inside an atom by the positive charge on the atom's nucleus. As a result, s orbitals, and p orbitals and even d and f orbitals always extend out from the atom's nucleus. Don't get so caught up in orbitals that you forget where they are and why they exist.

As with s orbitals, p orbitals can be big or small, depending on the value of n, and they can also have more or less nodes, also depending on the value of n. Notice, however, that unlike the s orbital, which can have no nodes at all, a p orbital always has at least one node. Take a look at the p orbital figure above again. Can you spot the node in each of the p orbitals? Since all p orbitals have at least one node, there are no p orbitals with n = 1. In fact, the first principal quantum number, n, for which p orbitals are allowed is n = 2. Of course you could have figured that out for yourself, right? No? Well, here’s a hint – remember the rules for predicting which values of ℓ are allowed for any given value of n. In the last lesson, you learned that ℓ must be no less than 0, but also, no greater than n − 1. For the n = 1 energy level, then, the maximum allowed value for ℓ is:

- maximum ℓ = n − 1

- maximum ℓ = 1 − 1

- maximum ℓ = 0

- maximum ℓ = n − 1

- maximum ℓ = 2 − 1

- maximum ℓ = 1

One interesting property of p orbitals that is different from s orbitals is that the total amount of electron density changes with both the distance from the center of the atom and the direction. Take a look at Figure 6.18. Notice how the electron density is different depending on which direction you travel from the center of the atom out. In the particular p orbital shown, the probability of finding the electron is greater as you head straight up from the center of the atom than it is as you head straight to the left or to the right of the atom. It turns out that this dependence on direction is very important when it comes to studying how different atoms interact and form bonds. We'll talk more about that in a later chapter.